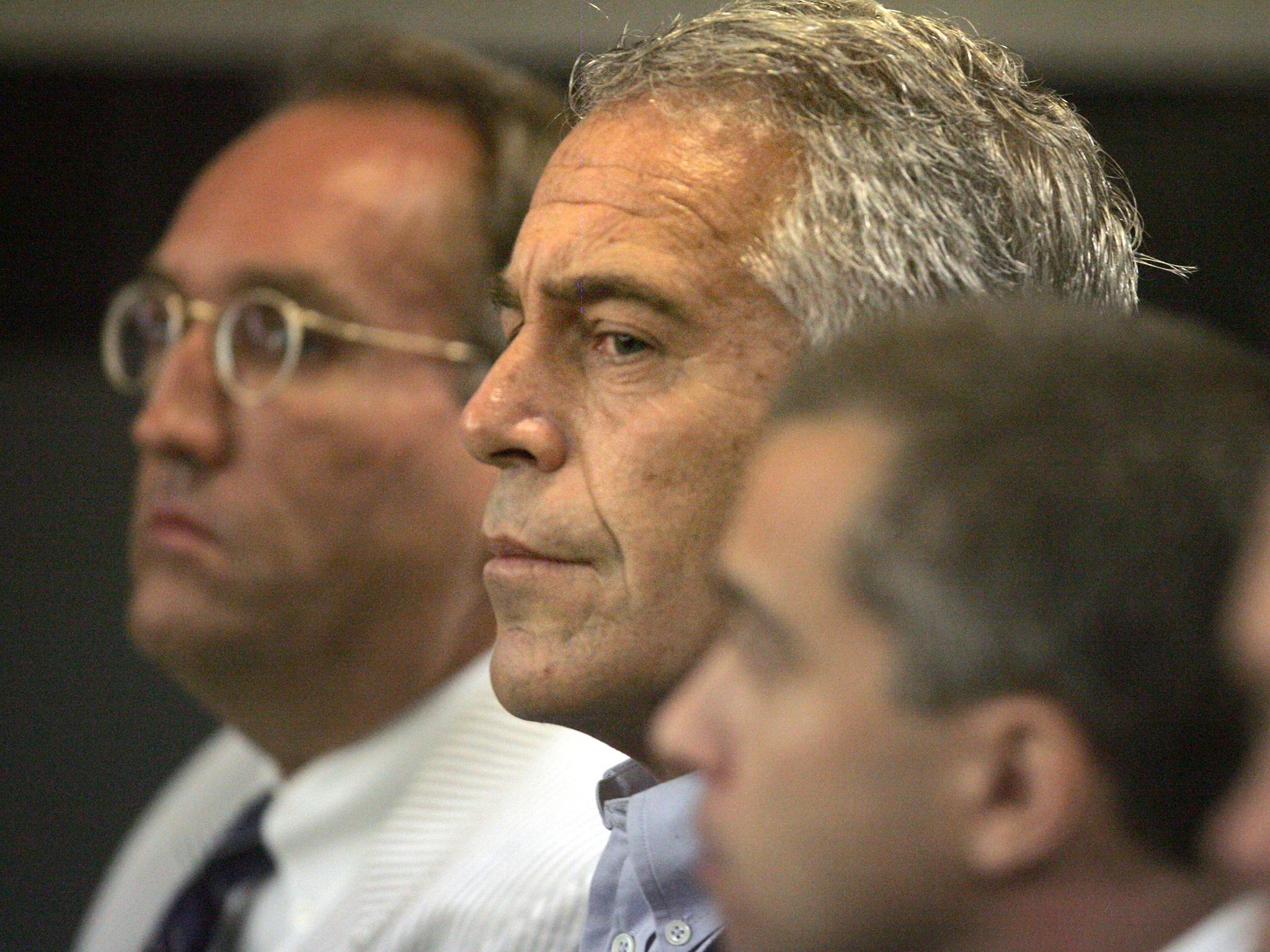

Jeffrey Epstein: Most court cases in US are resolved quickly and cheaply – but not always fairly

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Jeffrey Epstein first faced claims that he had abused multiple underage girls and hosted illicit sex parties for powerful men at his lavish home in Florida, onlookers might reasonably have expected him to face prison time of 10 or more years.

Instead, the disgraced financier agreed to plead guilty to the relatively minor charge of soliciting an underage girl for prostitution, for which he was given an 18-month sentence – he served 13 months – with a “non-prosecution agreement” promising that any alleged co-conspirators in Epstein’s dubious activities would be safe from criminal prosecution.

At the urging of his lawyers, the billionaire’s victims were not informed of the 2007 deal. But in July 2008, an appeals court found that Florida prosecutors had thus violated the US Crime Victims’ Rights Act (CVRA), ruling that “the government should have fashioned a reasonable way to inform the victims of the likelihood of criminal charges and to ascertain the victims’ views on the possible details of a plea bargain”.

Plea bargains are how the vast majority of criminal cases come to their conclusion in the US, with an agreement whereby the defendant consents to plead guilty in return for leniency from the prosecutor: earning, for instance, a lesser charge or a shorter sentence.

The recent allegations against Prince Andrew have arisen from a lawsuit brought by two women involved in the original case, in which they claim their rights under the CVRA were violated because they were not told about Epstein’s plea bargain.

In the US, plea bargaining is seen as a simple way for busy public defence lawyers, ambitious prosecutors and pragmatic judges to achieve a conviction quickly, without having to resort to a costly and time-consuming jury trial.

Elsewhere, however, the practice is often criticised on the grounds that its inherent balance of incentives and threats inevitably manipulates a defendant and can distort the proper outcome of a case.

The US legal system first came to rely on plea bargaining during the Prohibition years, when American cities were suddenly afflicted by fast-rising crime rates. In 2013, 8 per cent of all US federal criminal cases were dismissed, 3 per cent went to trial – and more than 97 per cent of the remainder were resolved with a plea bargain.

While plea bargaining is not part of the English legal system, defendants who do plead guilty are entitled under the sentencing guidelines to a reduced sentence.

Not unreasonably, it is thought that this public admission of guilt represents contrition, and that sparing the state the cost of a trial – and sparing witnesses the ordeal of giving evidence – is an act worthy of reward.

But it is hard to see how anyone was spared in Epstein’s case besides the billionaire himself, who, the lawsuit alleges, used his “significant social and political connections” – including with the former US President Bill Clinton – to arrive at a “more favourable” plea deal.